How to Overthrow a Dictator, Part 3

The pillars fall—and take the temple with it.

“I’ll be dead in an hour,” said the voice on the other end of the line.

It was less a prediction than a plea. The man who issued it, defense minister Juan Ponce Enrile, was in a world of trouble.

On February 22, 1986, at around three o’clock in the afternoon, Enrile placed a frantic call to Villa San Miguel, the residence of Cardinal Jaime Sin. Sin was the Philippines’ highest-ranking church official and a key player in the resistance.

“Your Eminence,” he implored, “please help us. The president’s men are coming to arrest us.”

Weeks earlier, Ferdinand Marcos, the country’s longtime dictator, had rigged a presidential election, deploying fraud and violence in an effort to barrel his way into another presidential term.

It was clear to everyone that he had lost to his opponent, Corazon Aquino. But he would not give up without a fight.

In the weeks since the vote, the world’s attention had been fixated on which of the two candidates would emerge victorious.

But Enrile had other plans. Together with Lt. General Fidel Ramos, the army vice chief of staff, he led a renegade faction of army officers, the Reform the Armed Forces Movement, known as RAM for short.

If it were up to them, there would be no President Marcos and no President Aquino, but a President Enrile. And they were going to do something about it.

Everything was set. The coup would take place at dawn on Sunday, February 23rd. Attacking from four directions, a RAM contingent would place the presidential palace under siege. At that point, another group would storm the residence, make a beeline for the master bedroom, and arrest the president and first lady. Then, they would announce to the nation that a military-led junta had taken charge.

The officers claimed that they were driven by outrage over rampant criminality and corruption in the military.

Such grandstanding was rather precious given the unsavory reputations of RAM’S leading members.

Consider some examples:

Lt. Vic Batac, who stood accused by an international commission of torturing a woman using “electric shock, water cure, sleep deprivation, sexual indignities, pistol whipping and threats to relatives.”

Lt. Rodolfo Aguinaldo, a “persistent and systematic torturer,” according to a Philippine rights organization.

Lt. Col. Gregorio Honasan, aka “Gringo,” implicated in “the brutal slaying of a dissident, Dr. Johnny Escandor, whose body was found dumped outside military headquarters in Manila, the brain removed from his skull and underpants stuffed in the cavity.”

Lt. Gen. Ramos, who, as head of the notorious Constabulary, had overseen the horrific abuses just described.

Finally, there was Enrile, the prime orchestrator behind martial law. Aside from terror, his other specialty was graft. Enrile was rumored to be the country’s third wealthiest man. This would have made him a billionaire—not bad for a guy on a government salary.

Considering the sorts of characters who made up RAM, it strains credulity to believe that they were acting out of moral indignation. These men had lost the right to be offended by anything.

The truth was far more banal: The officers were resentful at having been pushed aside by Marcos’s cronies—and they would now take back what was rightfully theirs.

There was a problem, however: Marcos had been tipped off to their plan and moved quickly to thwart it. A marine battalion was brought in to reinforce the palace, making it a death trap for any attackers. Worse, some of the key plotters were arrested just before the coup was to go into effect.

Forced onto the back foot, Ramos, Enrile, and the remaining RAM officers retreated to Camp Aguinaldo, the headquarters of the defense ministry, and Camp Crame, the seat of the national police. Both stood opposite one another on the eight-lane Epifanio de los Santos Avenue in Manila.

Marcos, who still controlled the bulk of the armed forces, was widely expected to order an assault on the rebel officers.

With no chance of overthrowing the president by force, their only hope was to call on the rest of the army to join their ranks—and rely on the crowds to defend them.

If they could somehow bring thousands of Filipinos onto the boulevard, the human mass could serve as a buffer against the president’s forces.

Without that, the RAM officers would be crushed—and everyone knew it. “A half-dozen shells and a few good strafing runs and we’re all dead,” affirmed one of Enrile’s colonels.

But there was a hitch: How to convince the people to risk their necks for a bunch of military officers with blood on their hands?

There was only one thing to do: place the call to Cardinal Sin. And so, in the evening of February 22nd, that is exactly what Enrile did.

By calling into question the regime’s survival, nonviolent action created the opportunity—and, very often, necessity—for the president’s allies to pull their support.

Sin, whose moral authority was matched by his political astuteness, immediately recognized the opportunity. The RAM officers would work their military networks to convince additional units to defect, while Sin would summon the faithful to their defense.

Even with Sin’s support, however, it would be a tall order to persuade Filipinos to rally behind their erstwhile torturers.

Hence, in an “act of contrition,” the two RAM leaders called a press conference for later that Saturday. There, seated beside Ramos, a visibly shaking Enrile announced his wish to atone for his crimes.

Well, maybe not all of them; now that he’s on the pyre, there’s no need to help pour the gasoline. But he did mention a few—his “participation in the declaration of martial law” and his more recent role in helping to rig the election in Marcos’s favor.

If only he’d known those sorts of things were frowned upon…

Ramos was somewhat less contrite, directing his fury at Marcos and his associates instead. The armed forces had become “immoral,” claimed the man who oversaw the use of electric shocks on the genitals of torture victims.

The performance was far from ideal. But the officers could still be useful to the revolution. For Cardinal Sin, that was enough.

Officers Schooled

Just hours before that fateful call, the RAM officers had been looking forward to a successful coup. Now, they were desperate, hoping against hope that their military colleagues would break ranks while ordinary Filipinos would come to their rescue.

In fact, the officers had just undergone a crash course in the nature of power. They had long been taught to see power as a fortress, insulated from the trivial concerns of everyday citizens. The only way to seize it, in this view, was to mount a superior military force that could overwhelm the ruler’s—exactly what they had planned to do in their coup.

But as they discovered, a coup is not the only or even most reliable way to oust a dictator. So, when the plot failed, they underwent a conversion. Very quickly, they came to understand that power is not at all like a fortress. It is more akin to a temple.

Recall the Pantheon of Rome, which could not stand without the support of its massive pillars.

Similarly, a ruler—even a dictator like Marcos—depends for his power on a set of pillars. The military and police are the most obvious ones. But he relies on other pillars too, such as prominent businesspeople, government officials, civil servants, pro-government parties, state media, religious authorities, and foreign allies.

As we saw in part two, Marcos had already lost some of these pillars long before the election took place: the Catholic clergy, for one, and the business community, for another. After the polls closed, he lost a third: the state election experts responsible for tallying the votes, who were now in open revolt over the fraud they had been asked to perpetrate.

But the most crucial pillars remained in his grasp—the military, first and foremost. The RAM officers only comprised a tiny portion of the armed forces, whose ranks, at this point, remained overwhelmingly loyal to the president.

The question was how to convince the rest of the army to defect. It would take a lot more than promises and sweettalking. Defying the president was an act of treason. For the soldiers who were still aligned with the regime, this was not a decision to take lightly.

For them, there was only one thing that could make the risk of defecting more tolerable. If the troops, commanders, and top brass could see that Marcos had lost his authority over the people, it would alter their calculus. Going against a ruler whose days were numbered was a different matter entirely than defying one who might remain in power indefinitely.

The RAM officers would work their military networks to convince additional units to defect, while Sin would summon the faithful to their defense.

Under those circumstances, in fact, the incentives would be reversed. If Marcos really was on his way out, his troops would have every reason to switch sides at the earliest opportunity—if only to avoid being implicated in any further crackdowns. After all, a new regime was on the horizon—and with it, the prospect of accountability.

Stand Down

Following Enrile and Ramos’s confessional, Sin issued a public appeal to “support our two good friends.”

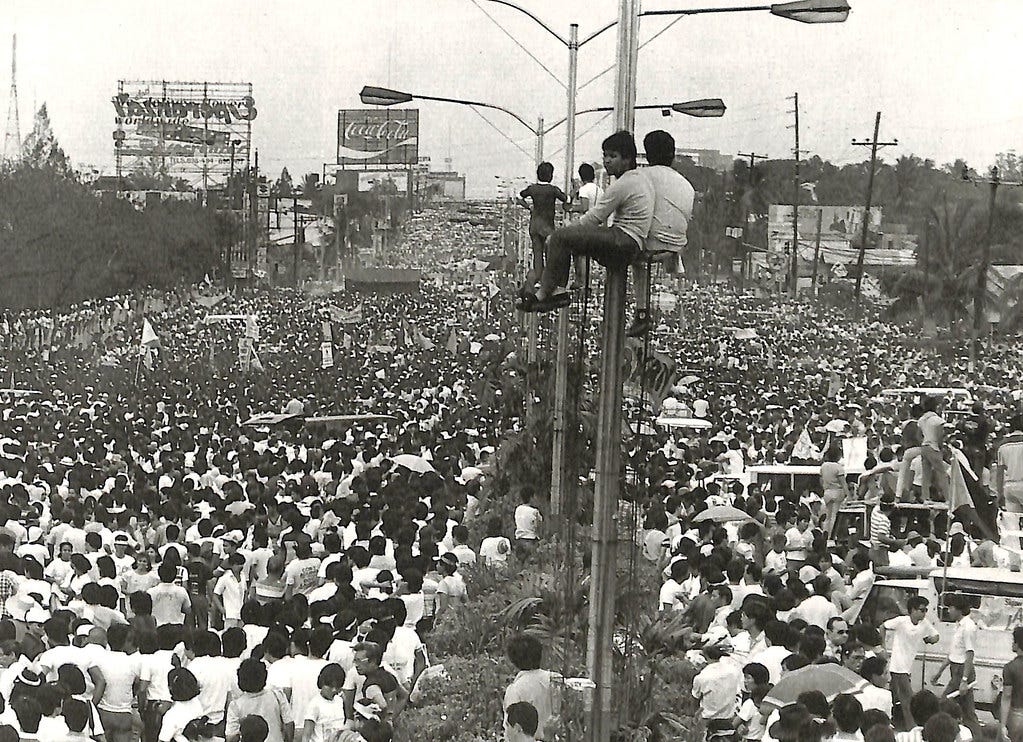

The effect was astounding. “By sunrise Sunday, the entire eight-lane width of Efran de Los Santos Street was choked with humanity,” reported Mark Fineman of the Los Angeles Times.

It was here, on the road to camps Crame and Aguinaldo, that masses of Filipinos confronted the regime’s armored columns. Epifanio de los Santos Avenue was now the key battleground in the struggle for the country’s future, and its acronym, EDSA, would become synonymous with the revolution.

For the next three days, EDSA was a giant festival grounds host to singing, dancing, and prayer vigils. At its peak, an estimated two million Filipinos—men and women, young and old, healthy and infirm—endured the threat of bloodshed to defend the rebel officers from Marcos’s troops.

Standing face-to-face with soldiers ordered to slaughter them, the demonstrators offered “flowers, chocolates, [and] prayers,” inviting them to switch sides and join the resistance.

“Stop! I am an old woman,” pleaded a wheelchair-bound protester in front of an armored personnel carrier. “You can kill me but don’t kill the young people here.” A moment later, a soldier descended, and they embraced.

Another woman placed her young granddaughter on top of a tank. The child kissed the driver, “and that finished the tank forever,” a witness recalls. “No anti-tank gun ever invented was so effective as that little three-year-old girl.”

Commanded to murder innocents, the soldiers flinched, and the people stood firm. “The funny thing about the whole siege,” recounts one participant, “was that all those [troops who were] ordered to attack Camp Crame, even if they were able to get through, ended up defecting to our side before they reached their target.”

During the entire four-day saga, not a single soldier intentionally killed a civilian.

But the wily Marcos had an ace up his sleeve. As it turned out, his most loyal devotee was not in any military command center but an ocean away, in Washington D.C.

America Teeters

“Three centuries in a Catholic convent and fifty years in Hollywood,” goes a common quip about Philippine history.

For three hundred years, the Catholic monarchs of Spain lorded over the Pacific archipelago. When they were not exploiting the people, they were busy converting them, turning the Philippines into Asia’s sole majority-Christian country.

In 1898, after its victory in the Spanish-American War, the United States assumed direct control of the islands. Such outright colonialism was unusual for the U.S., which preferred more informal means of domination. But it explains why American power continued to loom large in the country even after its independence in 1946.

During the Marcos era, America’s overriding concern was to protect its local military bases from a growing communist insurgency. To be sure, Marcos’s pitiless tyranny was responsible for fueling the rebellion in the first place. But U.S. policymakers, as they are wont to do, adopted an ass-backward reading of the conflict, viewing Marcos as the ultimate safeguard against a communist victory.

At the same time, the U.S. needed its strongman to at least pay lip service to human rights so as to avoid breeding opposition to the relationship at home and abroad.

But with Marcos ramping up the repression against Cory’s resistance movement, the fiction had become impossible to maintain. Images of bound, stabbed corpses in shallow graves did not play well on the NBC Nightly News. Congressional investigations were launched. Diplomats and national security officials started to question Marcos’s usefulness.

In this way, mass nonviolent action had laid bare the savage brutality at the regime’s core, making it ever more apparent to both Americans and Filipinos.

Filipinos reminded the world that dictators do not reside in fortresses. They instead sit atop temples, whose pillars can be knocked away.

Yet, there remained one holdout, and that holdout happened to be the president of the United States.

Ronald Reagan held Marcos in awe, a State Department official explained. It was as if the Philippine leader were “a hero on a bubble gum card he had collected as a kid.” To Reagan, Marcos was the valiant rebel who had fought against the Japanese in the Second World War, and the gracious leader who had rolled out the red carpet to him and Nancy when he was dispatched to Manila during the Nixon administration.

On the one hand, Marcos’s crimes, by this late date, had become too obvious to ignore. A week after the polls closed, Reagan publicly blamed his Filippino counterpart for the “widespread fraud and violence” that had occurred.

Still, he lacked the stomach to abandon Marcos altogether, even as his advisers were pushing for that very move.

For now, the president stood by his man.

Back in Manila, however, the resistance was taking on a life of its own, and regime defections were mounting as a result. Eventually, it would force even Reagan’s hand.

Downward Spiral

By Monday, February 24th, Marcos’s remaining allies had all but deserted him. His temple of power was on the verge of collapse, its supporting pillars in shambles.

And yet, he continued to play the part. In a nationally televised address, he vowed to “wipe out” his opponents. “If necessary, I will defend this position with all the force at my disposal.”

It was the last time he would speak before a national audience. Just as he announced a state of emergency, the rebels took control of the TV station, cutting him off mid-sentence. The feed switched over to Mel Lopez, an opposition deputy, who informed viewers that Marcos was “no longer the president of the Philippines.”

By this point, Marcos was a dictator in name only. He had lost the state media. He had lost his civil servants. He had even lost his airplane pilots, who, around three-o’clock am on the twenty-fourth, were seen speeding away from the presidential palace.

Most importantly of all, he had lost the military. Earlier that day, the crowds on EDSA beheld the terrifying sight of nine strike helicopters descending overhead. Only instead of assaulting Camp Crame, as they had been ordered to do, Burton writes, “the pilots jumped out, waving white handkerchiefs and flashing the Laban sign,” a symbol of resistance in which the thumb and index finger form an “L” for laban, or “fight.” “The anti-Marcos forces now controlled the skies.”

An attempt that same day to retake Channel Four, now in rebel hands, likewise disintegrated. When the soldiers arrived, they were met by protesters offering them coffee, donuts, and McDonald’s hamburgers. The commander promised to withdraw.

“The number of people still loyal to Marcos was shrinking with the passage of each second,” explain Jim Forest and Nancy Forest in Four Days in February, a book chronicling the regime’s demise. By Monday afternoon, 85 percent of the armed forces had defected to the rebels’ side.

Marcos met his end not at the hands of a superior military force but a society that stopped obeying him.

When the day ended, Marcos stood alone. Even Reagan had to bow to the inevitable. “Attempts to prolong the life of the present regime by violence are futile,” read a White House statement. “A solution to this crisis can only be achieved through a peaceful transition to a new government.”

It was as good as an obituary.

When Marcos saw the announcement in the early morning of February 25th, Manila time, he phoned U.S. Senator Paul Laxalt, who had played a key role in the diplomacy surrounding the crisis. Marcos wanted to be sure that the statement reflected the position of the U.S. government. Karnow describes the exchange:

“Senator,” Marcos pressed, “what do you think? Should I step down?” Laxalt responded without hesitation: “I think you should cut and cut cleanly. I think the time has come.” There was a silence so long that Laxalt, wondering whether they had been disconnected, asked, “Mr. President, are you there?” “Yes,” responded Marcos in a thin voice. “I am so very, very disappointed.”

The next day, Cory Aquino had her swearing-in at the private Club Filipino. Instead of taking power themselves, as they had originally planned, Enrile and Ramos were seated among the attendees. Whatever the two powerbrokers’ ambitions, the Philippine people had their own plans.

An hour later, Marcos held an inauguration for himself behind the fortified walls of the presidential palace. It was a pathetic affair with sparse attendance. His prime minister, who earlier that day had been replaced by a member of the opposition, did not show up. Neither did his vice-presidential candidate.

It was time to say goodbye. But the ruling couple would not be denied one last performance. “Show biz to the end, Marcos and Imelda stepped out onto a palace balcony, peered at a crowd of supporters and hecklers, and sang a farewell duet: ‘Because of You.’”

One gets the impression that they would have relinquished power years earlier had they been offered the lead roles in Splash (1984).

After wrapping up, the Marcoses and their entourage boarded a small fleet of U.S. military helicopters, which took them to a nearby base. From there, they were flown to Hawaii, where they owned a mansion overlooking Honolulu, part of an extensive U.S. property portfolio unwittingly financed by the Philippine people.

In a final show of loyalty, Reagan had offered them asylum.

Into Pieces

“I do not ask that you place hands upon the tyrant to topple him over, but simply that you support him no longer,” wrote Étienne de La Boétie in 1577. “[T]hen you will behold him, like a great Colossus whose pedestal has been pulled away, fall of his own weight and break into pieces.”

Four centuries later, Filipinos took him up on that advice.

The anti-Marcos revolution introduced a new term to the global lexicon: “people power.” It was both a description of the events and a revelation on the part of everyday citizens—that they, not some self-appointed tyrant, were the ones who controlled their destiny.

Filipinos reminded the world that dictators do not reside in fortresses. They instead sit atop temples, whose pillars can be knocked away.

Gene Sharp explains the difference:

One can see the power of a government as emitted from the few who stand at the pinnacle of command. Or one can see that power, in all governments, as continually rising from many parts of the society.

One can also see power as self-perpetuating, durable, not easily or quickly controlled or destroyed. Or political power can be viewed as fragile, always dependent for its strength and existence upon a replenishment of its sources by the cooperation of…institutions and people—cooperation which may or may not continue.

In February 1986, Filipinos proved which one of these views is correct.

Through strikes, protests, and other forms of nonviolent resistance, the people withdrew their consent to be ruled. As a consequence, the elites who had once served as pillars of Marcos’s regime abandoned him.

Different elites acted for their own reasons—the Catholic clergy out of moral revulsion; the business community to protect its interests; military officers to gain political advantage; ordinary soldiers to avoid complicity; and the U.S. government to secure its bases.

In the final analysis, however, it was mass nonviolent resistance which pushed, pulled, moved, implored, threatened, and enabled those elites to act. By calling into question the regime’s survival, nonviolent action created the opportunity—and, very often, necessity—for the president’s allies to pull their support.

Marcos met his end not at the hands of a superior military force but a society that stopped obeying him. By the simple act of noncompliance, everyday resisters had consigned his regime to ashes.

Americans, pay heed.

Other Entries in this Series

How to Overthrow a Dictator, Part 1

How to Overthrow a Dictator, Part 2

Sources

Amnesty International. 1976. Report of an Amnesty International Mission to the Republic of the Philippines: 22 November-5 December 1975. Amnesty International Publications.

Branigin, William. 1986. “Rebels, Marcos Contest Control of Philippines.” The Washington Post, February 23. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1986/02/24/rebels-marcos-contest-control-of-philippines/2c18fa71-45dc-423f-a3e1-9cd187dec323/, accessed January 15, 2026

British Broadcasting Corporation. 2006. “From Dictatorship to Democracy.” BBC News, February 14. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/documentary_archive/4713466.stm, accessed February 3, 2026.

Burton, Sandra. 1989. Impossible Dream: The Marcoses, the Aquinos, and the Unfinished Revolution. Warner Books.

Chenoweth, Erica and Maria Stephan. 2011. Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict. Columbia University Press.

Dalton, Keith. 2025. Reinventing Marcos: From Dictator to Hero. Lightning Source Global, Amazon Publishing, and IngramSpark. Kindle.

de La Boétie, Étienne. 2016 [1577]. Discourse on Voluntary Servitude: Why People Enslave Themselves to Authority, edited by William Garner. Adagio. Kindle.

Fineman, Mark. 2026. “The 3-Day Revolution: How Marcos Was Toppled.” Los Angeles Times, February 27. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1986-02-27-mn-12085-story.html, accessed January 26, 2026.

Forest, Jim and Nancy Forest. 1988. Four Days in February: The Story of the Nonviolent Overthrow of the Marcos Regime. Marshall Pickering.

Karnow, Stanley. 1989. In Our Image: America’s Empire in the Philippines, Ballantine Books and Random House. Kindle.

McCoy, Alfred W. 1990. “Philippine Military ‘Reformists’: Specialists in Torture.” Los Angeles Times, February 4. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-02-04-op-202-story.html, accessed February 12, 2026.

McCoy, Alfred W. 1999. “Dark Legacy: Human Rights Under the Marcos Regime.” Paper presented at the Legacies of the Marcos Dictatorship Conference, Ateneo de Manila University, September 20. http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/54a/062.html, accessed January 9, 2026.

Nemenzo, Gemma. 2016. “30 Years Ago: Coup d’etat and People Power.” Positively Filipino, February 24. https://www.positivelyfilipino.com/magazine/30-years-ago-coup-detat#:~:text=What%20it%20was%20in%20unadorned,decent%20elements%20of%20the%20KBL, accessed February 12, 2026.

Rappler.com. 2025. “Listen: Cardinal Sin’s 1986 Appeal for Filipinos to Go to EDSA, Support Ramos and Enrile.” February 22. https://www.rappler.com/philippines/audio-jaime-cardinal-sin-1986-appeal-go-edsa-support-fidel-ramos-juan-ponce-enrile/, accessed February 3, 2026.

Seagrave, Sterling. 2018. The Marcos Dynasty. Lume Books. Kindle.

Sharp, Gene. 2006 [1973]. The Politics of Nonviolent Action. The Albert Einstein Institution. Kindle.