How to Overthrow a Dictator, Part 2

The ground beneath the temple shakes.

“The whole place is gonna go. It’s gonna pop like a cork.”

—TIME correspondent, Manila, August 21st, 1983

On the flight to Manila, Ninoy’s mood alternated between tense and serene.

That morning, he boarded a Boeing 767 en route from Taiwan. Clad in the same white suit he wore the day he left the Philippines three years earlier, he passed the time chatting amicably with his entourage and the retinue of journalists accompanying him.

One of those reporters was Sandra Burton, whose narrative of the event provides the basis for its retelling here.

Burton spoke extensively to Ninoy during the trip. “They say the guy is stupid to go home,” he told her, referring to himself in the third-person. “They don’t understand the value of self-sacrifice. Gandhi kneeling down and getting bashed. The vanquished is the victor. If you can get at the bad thing within your enemy, you unmask him.”

The plane begins its approach. Through the window, Ninoy catches sight of the verdant mountains of northern Luzon. “I’m home,” he declares elatedly.

A stewardess grabs the microphone. “At twelve-forty-five P.M., it is eighty-eight degrees Fahrenheit in Manila. We hope you have enjoyed your flight and will fly again soon with China Airlines.”

The cabin crew approaches to wish Ninoy well.

“1:04 P.M., touchdown,” Burton writes in her notebook. “Machine guns and tanks near the terminal.”

The plane rolls to a stop. The pilot comes on the loudspeaker. “Please remain in your seats for ten minutes.”

Through the window, a blue van can be seen backing up to the stairs leading from the jet bridge to the tarmac.

Three soldiers enter the plane and start down the aisle. After spotting Ninoy, they help him up, grab his bag, and escort him to the exit door.

As soon as they leave, the remaining passengers line up, waiting to disembark.

Voices can be heard from the jet bridge:

Person 1: I’ll do it!

Person 2: They can have it!

Person 3: Get down, get down!

Then, from just outside the service door to the tarmac, a loud pop.

TIME correspondent: What happened? What was that?

Three more shots. A female passenger screams. Another pop.

TIME correspondent: Wait. What happened? Oh no, he’s…

Female passenger: Oh no [wails]

ABC-TV correspondent: What happened?

TIME correspondent: The soldiers…they put about sixteen shots in him. They shot Ninoy. He’s dead out there. Christ, almighty…

A team of SWAT commandos stands on the tarmac, guns aimed at the passengers as they descend the stairs. A few of the soldiers approach Ninoy’s body as it lies lifeless on the ground. They pick it up and fling it into the blue van. Then, they jump in the back, and the van speeds off.

Left behind is a second man, dead in a pool of blood.

TIME correspondent: Does anybody know what those uniforms were?

Japanese reporter: They pretend that this guy killed him…Goddamn Philippines.

TIME correspondent: The whole place is gonna go. It’s gonna pop like a cork.

The Cork Pops

Known affectionately as “Ninoy,” Benigno Aquino was outgoing and charismatic. He could “sway crowds like a snake charmer,” Burton recalls.

Though born into one of the Philippines’ most privileged families, he was taught from a young age to help those in need. The emphasis on charity was unusual for someone of his class. It would later serve him well as a politician, helping him cultivate a man-of-the-people image.

As governor of one of the only provinces not under Marcos’s control, Aquino was arrested soon after martial law was declared in 1972. He spent the rest of the decade languishing in prison. Under American pressure, he was released into exile in the U.S. in 1980. There, he remained for three years before returning that fateful day in August 1983, his mind set on a political comeback.

By ordering Aquino’s assassination, Marcos had miscalculated—badly. True, he had rid himself of his longtime nemesis and primary electoral threat. But far from shoring up his regime, he had set in motion forces that would lead to its collapse.

Marcos’s allies had a choice to make: stay loyal to the president and risk facing accountability, or switch their allegiance to Aquino, the legitimate president-elect. For them, it was about self-preservation.

Like most of us, Marcos subscribed to a common myth about power—that the ruler, protected by his army and police, can freely impose his will on society.

Power, in this conception, is like a fortress—strong, durable, and insulated against any foes. The only way to dislodge a leader like Marcos is by destroying his fortress with a superior army or taking control of it in a coup.

But the fortress view is misleading, we saw last time. The dictator, after all, is just one person. To remain in power and enforce his dictate, he needs the support of a whole range of elites. These include, first and foremost, the military and police. But he also depends on prominent businesspeople, government officials, civil servants, pro-government parties, state media, religious authorities, and foreign allies.

In this regard, power is more accurately viewed as a temple than a fortress. The Pantheon in Rome would not remain upright without the support of its columns, or pillars. Topple those pillars and watch it collapse.

The question, for those suffering under the dictator’s rule, is how to knock those pillars down. Nonviolent resistance is by far the most effective way.

Nonviolent action creates the opportunity—and, often, necessity—for the ruler’s supporting pillars to cut and run, leaving him bereft of the agents he depends on to wield control.

Some of these defectors act because they fear accountability if the regime falls. Others see opportunities for advancement. Either way, the removal of their support deprives the ruler of the very sources on which his power rests.

As Marcos gazed upon the image of Ninoy’s bullet-riddled corpse, he surely believed that his fortress had been strengthened.

Little did he know, he was living in a mirage.

Marcos did not reside in a fortress at all, it turns out. Instead, he was sitting on the roof of the Pantheon. And the ground beneath had just begun to shake.

Tremors in the Temple

“I want people to see what they did to my son,” a furious Aurora Aquino roared.

Even in grief, her political savvy was evident. There would be no closed casket. The public would bear witness to her son’s disfigured corpse, dressed in the same blood-drenched suit he wore the day of his murder—a grisly testament to the crime, an accusation embodied in flesh.

The funeral, his mother declared, marked Ninoy’s “resurrection,” a fitting postscript to his “crucifixion” on the airport tarmac. Aurora instinctively grasped the sort of imagery which resonated in the devoutly Catholic Philippines.

As the coffin made its way through the streets of Manila, more than a million onlookers gathered to watch. The color yellow, long associated with the Aquino family, was visible everywhere—on clothing, banners, ribbons, flowers.

While no one knew it at the time, Ninoy’s procession marked the starting gun of a movement. For the next three years, Manila was the scene of strikes, demonstrations, and other forms of nonviolent resistance that would eventually force the Marcoses into exile.

Just as unexpected as the movement itself was the person who emerged at its head: Ninoy’s widow, Corazon.

Although the role had largely been thrust upon her, Cory, as she was known, turned out to be more than her husband’s equal when it came to moving a crowd. “It seemed,” writes Stanley Karnow, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning In Our Image: America’s Empire in the Philippines, that she “was in direct communion with the people, projecting an aura of sanctity that almost mesmerized devout Filipinos.”

In time, most of the country’s fractious opposition would unite behind her.

Far from demoralizing Filipinos, the ruthless violence that Marcos meted out in response only emboldened them. The 1984 parliamentary elections drew a turnout of ninety percent. Parties backed by Cory surmounted colossal fraud and intimidation to win a third of the seats.

The following year, in February 1985, the assassination of a labor leader sparked a general strike. That same month saw thousands of farmers embark on a 200-mile trek from Luzon to Manila to hold a nine-day sit-in outside the agriculture ministry.

Further inflaming public anger was the sham verdict in the trial of Ninoy’s assassins. In December 1985, army chief Fabian Ver, a Marcos loyalist and the country’s second most powerful figure, was acquitted with his co-conspirators of planning and executing the murder.

The First Pillars Give Way

Marcos’s repression was clearly backfiring. With every arrest, beating, and murder, the resistance grew, and he was powerless to stop it.

The veil of invincibility had been lifted, revealing an embittered and impotent man lashing out in futility.

Now that the end of his rule seemed like a real possibility, his erstwhile allies began to reassess their support.

The Catholic Church had never backed the regime outright. But in a country as devout as the Philippines, the clergy held considerable sway. At the very least, it was imperative for Marcos that they remain acquiescent.

Yet, the routine torture and murder of clergy members did not exactly help his cause. As the abuses mounted, many became vocal opponents.

Chief among these critics was Cardinal Jaime Sin, the country’s highest ranking church figure. Sin would play a key role in Marcos’s downfall. A skilled organizer and communicator, he was more responsible than anyone save Cory Aquino for uniting the opposition. Under his leadership, the church trained thousands of volunteer election monitors as well.

The church-owned Radio Veritas was far and away the country’s most important independent media outlet. As the resistance gained force, Radio Veritas served as both a critical source of information and a coordinator of mass action.

More important still were the nuns. It was they who stood between the demonstrators and the soldiers, calming jittery nerves and keeping both sides peaceful. “When the tanks started to move, they didn’t budge,” recalls one observer. “They just kept praying.”

While the clergy acted on principle, others saw in the burgeoning movement a chance to gain advantage.

Marcos’s corrupt predation and economic mismanagement had already alienated most of the business elite. During martial law, he subjected scores of businesspeople to sham prosecutions, which he used as pretexts to seize their assets and gift them to his cronies in exchange for kickbacks.

Thanks to such schemes, Marcos amassed a fortune worth at least $10 billion dollars by the end of his presidency, which he stashed away in a maze of bank accounts and properties in Switzerland, Hong Kong, and the U.S.

Adding insult to injury were his multibillion-dollar bailouts of these same cronies once the economic crisis of the early 1980s hit, even as traditional business elites saw their fortunes crater.

In 1981, a collection of business executives formed the Makati Business Club, which would serve as an advocacy group to press for their interests. At the same time, most businesspeople steered clear of overt opposition to the regime.

Ninoy’s assassination was the breaking point. It not only showed that their own lives were expendable, but the resulting surge in popular resistance convinced them that Marcos could be defeated. From 1983 onwards, the Makati Business Club poured its resources into the opposition movement.

On their own, the clergy and business community lacked the heft to threaten the regime, whose weightier pillars remained standing. In February 1986, these other pillars would fall, too, taking Marcos with them.

A Forced Choice

Dictators would survive much longer but for one common flaw: Eventually, they start to believe their own bullshit.

At the same time that First Lady Imelda Marcos was lecturing her courtiers about a “cosmic vision of development,” she was raiding a typhoon relief fund to pay for her daughter’s wedding.

Ferdinand was equally oblivious. “His corrupt administration was totally discredited by late 1985,” Karnow writes, “yet his blind belief in his own invincibility prompted him to schedule the election against Cory Aquino that spelled his doom.”

High on his own supply, Marcos called the snap poll for February 7th, 1986, certain that he could fraud his way to victory just as he had in the past.

He failed to understand just how fundamentally the country’s politics had changed. Through the experience of civil resistance, a public that was once overawed by his intimidation and propaganda had become cognizant of its own power.

Filipinos were about to seize the future for themselves. In the process, they would drag down the remaining pillars that kept his temple standing.

Nonviolent action creates the opportunity—and, often, necessity—for the ruler’s supporting pillars to cut and run, leaving him bereft of the agents he depends on to wield control.

With little time to lose, the opposition quickly united behind Cory Aquino. Marcos and his thugs, for their part, drew generously from their ratfucking repertoire, stuffing ballot boxes and unleashing wanton violence.

This time, it would not work. Two days after the voting ended, on February 9th, the computer technicians responsible for tallying the votes walked off the job in protest at the ongoing fraud. Another pillar had fallen.

Days later, on the fourteenth, over a hundred Catholic bishops denounced the “unparalleled” election violations, proclaiming Marcos’s bid to remain president as having “no moral basis.”

When the parliament, stacked with pro-government loyalists, declared Marcos the winner the next day, the opposition walked out.

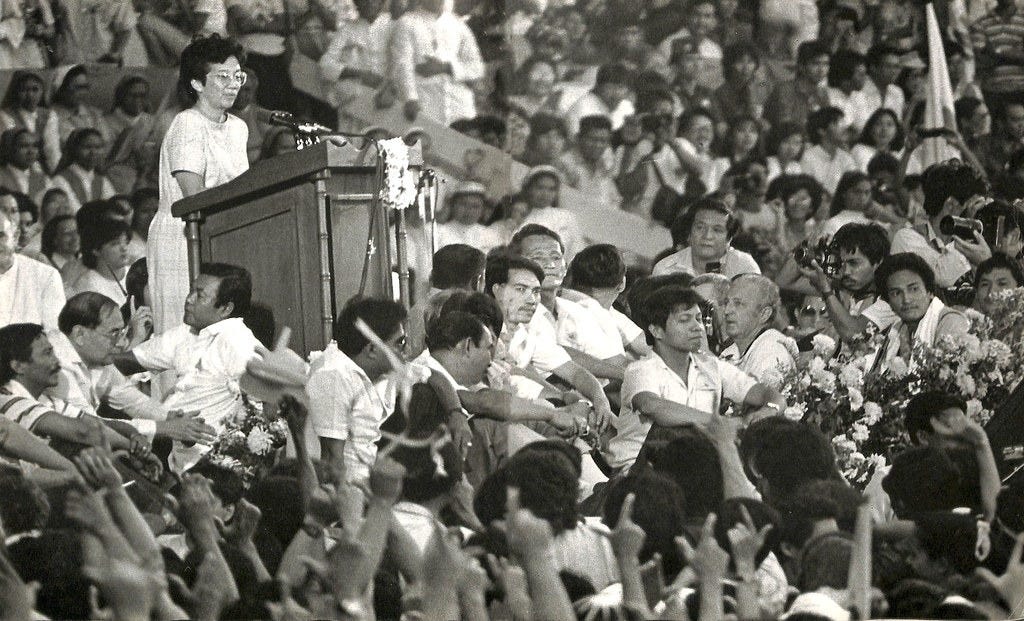

The sixteenth brought one of the revolution’s pivotal events. Two million Filipinos gathered at Manila’s Luneta Park to hear Cory Aquino speak. The sheer size of the turnout was an unmistakable sign that Philippine society, or a massive part thereof, rejected Marcos’s legitimacy.

For the first time in twenty years, the prospect of his downfall went from distant possibility to imminent prospect.

In her address, Aquino called for a nationwide campaign of civil disobedience, to include mass demonstrations and boycotts of businesses, banks, and media outlets that supported the president.

Any allies who remained by Marcos’s side now had a choice to make. They could stay loyal to the president and risk facing accountability if he fell. Alternatively, they could switch their allegiance to Aquino, the legitimate president-elect, and retain some chance of maintaining their influence and freedom once she took over.

Morality, for them, had nothing to do with it. This was about self-preservation. And it was thanks to the courage of everyday Filipinos that they faced this dilemma in the first place.

Next time, the revolution reaches its crescendo, forcing the temple’s two most important pillars to give way.

Sources

Branigin, William and John Burgess, “Fraud Charges Multiply in Philippines,” The Washington Post, February 9, 1986, https://wapo.st/4qsMGU4, accessed February 10, 2026

Burton, Sandra, Impossible Dream: The Marcoses, the Aquinos, and the Unfinished Revolution (New York, Warner Books, 1989)

Chenoweth, Erica and Maria Stephan, Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011)

Forest, Jim and Nancy Forest, Four Days in February: The Story of the Nonviolent Overthrow of the Marcos Regime (Hampshire, U.K.: Marshall Pickering, 1988)

Karnow, Stanley, In Our Image: America’s Empire in the Philippines, Kindle Edition (New York and Toronto: Ballantine Books and Random House, 1989)

Nepstad, Sharon Erickson, Nonviolent Revolutions: Civil Resistance in the Late 20th Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011)

Schock, Kurt, Unarmed Insurrections: People Power Movements in Nondemocracies (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005)

Sharp, Gene, The Politics of Nonviolent Action (Boston: The Albert Einstein Institution, 2006 [1973])

“Text of Filipino Bishops’ Statement on Vote,” New York Times, February 15, 1986, https://www.nytimes.com/1986/02/15/world/text-of-filipino-bishops-statement-on-vote.html?smid=url-share, accessed January 14, 2026

Thompson, Mark R., The Anti-Marcos Struggle: Personalistic Rule and Democratic Transition in the Philippines (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995)

Tran, Mark and Nicholas Cumming-Bruce, “From the Archive, 17 February 1986: Protest at President Marcos’ Election Victory,” The Guardian, February 17, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2014/feb/17/philippines-ferdinand-marcos-corazon-aquino, accessed February 11, 2026

Zunes, Stephen, “The Origins of People Power in the Philippines,” in Stephen Zunes, Lester Kurtz, and Sarah Beth Asher, eds., Nonviolent Social Movements: A Geographical Perspective (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1999)

"By ordering Aquino’s assassination, Marcos had miscalculated—badly. True, he had rid himself of his longtime nemesis and primary electoral threat. But far from shoring up his regime, he had set in motion forces that would lead to its collapse."

Now contrast this to the tiny whimper of discontent when Putin murdered Navalny, and it becomes obvious that the modern dictatorship (at least in Russia, China, Iran etc) is built on far sturdier stuff. If the common people hardly give a fig the dictatorship can survive a lot, but even if they mostly all hate the regime, as long as the troops stay loyal they can still survive.