Occupation is Always Bad, Actually

An idea which shouldn't be controversial evidently is.

Is it ever okay to violently subjugate others? One would think not. And yet the question somehow manages to provoke disagreement.

Consider the two biggest stories in the world: Russia’s war on Ukraine and Israel’s war on Gaza.

Both involve an attempt to occupy an unwilling population. Both have given rise to innumerable apologists who argue that occupation is either good in itself or an unfortunate necessity. Incredibly, many of the same people who oppose occupation in one case seem perfectly fine with it in the other.

Ukraine and Palestine are obviously very different. But in one fundamental respect—the presence of a state acting to brutally dominate an entire people—they are the same. No amount of qualification can obscure this basic fact.

Split-Brained and Aimless

Consider Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It is, quite straightforwardly, a war of colonial conquest. It has also spawned a cottage industry of pundits and influencers who argue that Russia’s annexation of Ukrainian land must be accepted.

Proponents of such “solutions” range from fringe-conspiracy theorists such as Michael Tracey and Aaron Maté to once-esteemed academics like John J. Mearsheimer and Jeffrey Sachs. All of them invoke any number of spurious and easily-refutable reasons—whether Ukrainian Nazis or NATO or the plight of Russian-speakers or the Euromaidan “coup” or “ending the suffering” or the threat of nuclear war—why Ukraine and the world must resign themselves to Russia’s colonial ambitions.

Now because the word “occupation” conjures up all sorts of unpleasant images, its advocates prefer to call it “peace” instead. Who, after all, could argue against peace? The problem is, any “peace deal” would require Ukraine to surrender large swathes of its own territory along with millions of its unwilling inhabitants to permanent Russian control. This is not my opinion; it is the official stance of the Russian Federation. And going by Russia’s record as an occupier, “peace” is the last thing these people will experience.

Take Stephen Walt, the Robert and Renee Belfer Professor of International relations at Harvard’s Kennedy School. In September of this year, he wrote:

The moral case for pursuing peace—even if the prospects are unlikely and the results are not what we’d prefer—lies in recognizing that the war is destroying the country and that the longer it lasts the more extensive and enduring the damage will be. Unfortunately for Ukraine, anyone who points this out and offers a serious alternative is likely to be loudly and harshly condemned and almost certain to be ignored by the relevant political leaders.

The problem, I would suggest, is not that Walt and his ilk get criticized. The problem is that they do not listen to what their critics are saying. Walt and others have time and again put forth their “moral case for peace.” What they haven’t made is their moral case for occupation. What is Walt’s argument for forcing Ukraine to accept an eternity of mass-executions, deportations, filtration camps, and torture chambers for millions of its citizens who are involuntarily consigned to Russian rule?

The fact that “peace” would mean occupation and occupation more and more atrocities should be obvious to anyone acquainted with Russia’s post-Soviet history, not to mention its earlier record. Ukrainians certainly are, which is probably why opinion polls have consistently shown at least 85 percent of them opposed to a land-for-peace deal.

Not every Ukrainian is familiar with Russia’s barbaric conduct in places such as Chechnya and South Ossetia. There, the cessation of armed conflict merely marked the beginning of the savage repression their populations endured. But they certainly remember their own history of brutal Russian colonialism, whether the manufactured Soviet famine which deliberately starved millions of their forebears or the merciless subjugation of Crimea, the southern Ukrainian peninsula Russia has occupied since 2014.

Walt and his fellow-travelers not only insist on policies that threaten to permanently deprive Ukrainians of life and liberty; they have the gall to excoriate them for their supposed strategic myopia. “If we are talking about human lives,” Walt argues in the same essay, “we must look beyond abstract principles and consider the real-world consequences of different choices.”

Indeed, we must; only in evaluating the costs and benefits of war versus “peace,” Walt and others like him ignore the costs and benefits of war versus occupation.

Amazingly, the very same people who blind themselves to the reality of Russian occupation tend to be remarkably lucid on the matter of Israeli occupation. Take Jeffrey Sachs. In a recent article subtitled, “friends do not let friends commit crimes against humanity,” Sachs agreed with the view of multiple human rights organizations that “Israel’s occupation of Palestine is tantamount to apartheid.”

Yet he seems perfectly fine with occupation so long as its victims are Ukrainians instead of Palestinians. “The basis for peace [in Ukraine] is clear,” he wrote in February. “A practical solution would be found for the Donbas, such as a territorial division, autonomy, or an armistice line.” Exactly what that would entail for the Ukrainians who live there is a question he neglects to consider.

Walt and Mearsheimer, too, have no problem acknowledging the moral reprehensibility of Israel’s occupation. In their previous coauthored work, they condemned America as “the de facto enabler of Israeli expansion in the occupied territories, making it complicit in the crimes perpetrated against the Palestinians.” Yet both scholars are among the most vocal proponents of a similar and arguably worse occupation of Ukraine.

Equally vexing as the people who decry occupation in Palestine but not in Ukraine are their opposite—those who denounce occupation in Ukraine but defend it in Palestine.

David Frum has been an outspoken supporter of Ukraine since the beginning, slamming Russia’s “atrocity and genocide” and urging the West to help Ukraine repel the invasion.

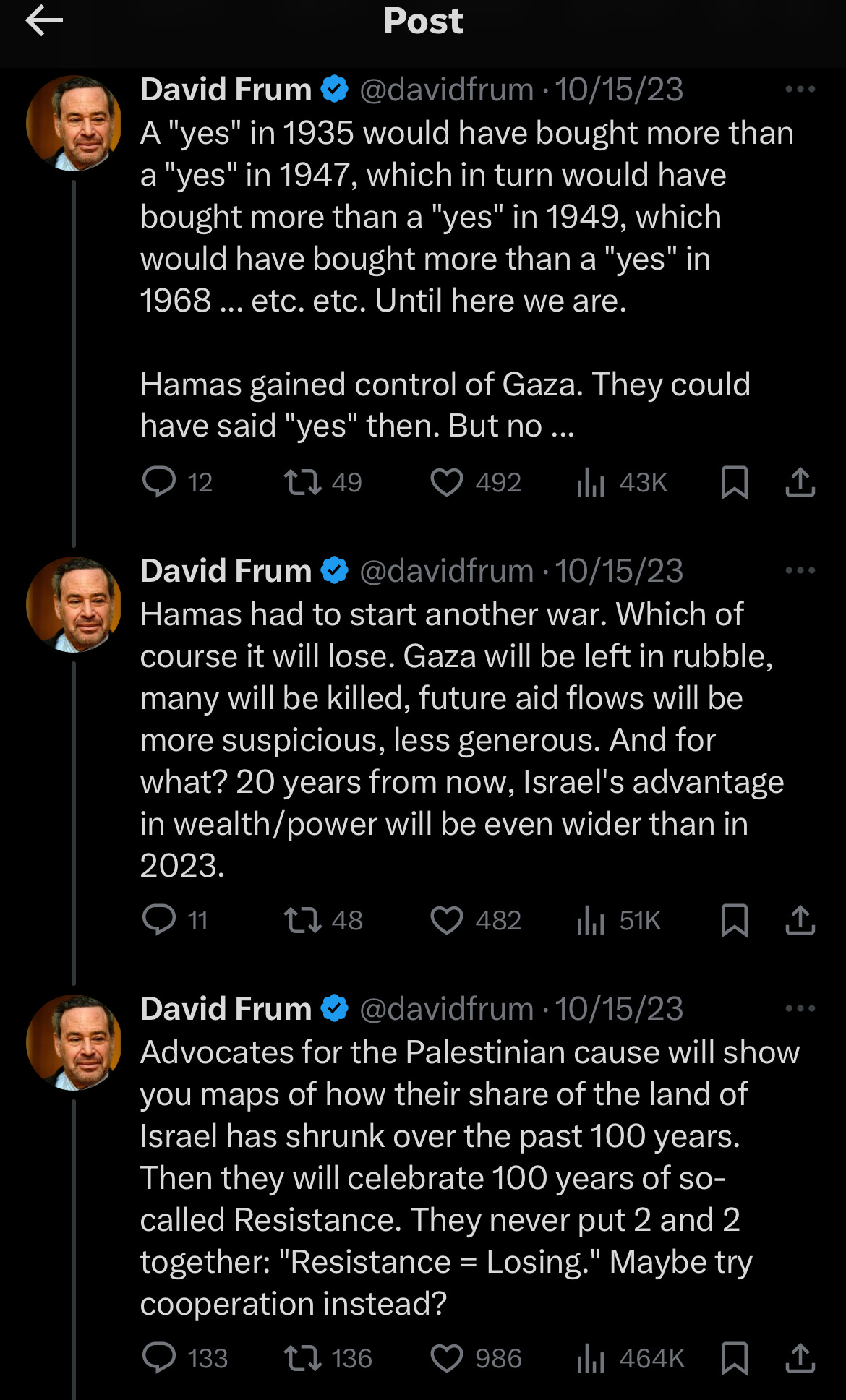

But his moral clarity on Ukraine appears to be lacking when it comes to Israel and the Palestinians. In the tweets below, for instance, he criticizes “advocates for the Palestinian cause” for what he regards as their futile and counterproductive resistance to occupation. If only they cooperate with their occupier, he suggests, they might actually win the very state they have long sought:

It is hard to imagine Frum entertaining such victim-blaming rationales for Russia’s occupation of Ukraine.

Frum has a history of trivializing Palestinian rights. In a 2010 article, he accepts on its face Israel’s refusal to allow the return of millions of Palestinian refugees—this despite the fact that Israel itself bears much of the responsibility for causing their flight in 1948. Instead, he insists, the burden of accommodating them rests with the neighboring Arab states where they now reside and which have refused to grant them citizenship.

To take another example, in a 2012 video he advises the next U.S. president to avoid getting involved in negotiations over a Palestinian state in part by downplaying its importance to the Palestinians. It is, he says,

certainly not important enough for the Palestinians ever to make any real compromise on the issue. If you want something badly enough, you make compromises even if they’re unpleasant, and in 2000 we saw that, on the core issues in dispute, the Palestinians will not compromise. So it’s not that important to them.

Frum’s willingness to accept the occupation and ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians stands in sharp contrast to his uncompromising stance on Ukraine, where he supports resistance to Russian conquest without qualification.

Frum is hardly the only prominent voice who opposes Russia’s occupation of Ukraine while defending its equivalent in Palestine. Consider former GOP representative Adam Kinzinger. A guy who proudly displays the slogan “Slava Ukraini” alongside the Ukrainian flag in his Twitter profile evidently sees Palestinians as less worthy of support. In fact, he has explicitly backed Israel’s efforts to collectively punish them for Hamas’s crimes:

An Enduring Myth

Whichever community whose occupation they selectively justify, both sides invoke their own Very Good Reasons to bolster their positions. I have already dealt at length with the justifications put forth by the “Russian Occupation is Okay” school. As for their counterparts in the “Israeli Occupation is Okay” camp, I discussed some of their excuses in my most recent post. It is worth examining a few additional ones here.

One argument they frequently advance, and to which Frum alludes above, is the idea that the Palestinians had their chance at a state only to stubbornly turn it down. This fact is somehow supposed to justify continued Israeli occupation.

In 2000, the Clinton administration attempted to broker a peace deal at Camp David, but the two sides could not reach an agreement. Then, in December of that year, Clinton issued a proposal—the now-famous “Clinton Parameters”—which attempted to bridge the gap.

According to Clinton himself, the Israeli delegation accepted the parameters, albeit “with reservations.” But, he claims, the Palestinian side rejected them outright.

The notion that Israel was prepared to give the Palestinians a state only for the Palestinians to spurn it has dominated much of the public perception of the peace process ever since. It is a story that Israel has embraced, for obvious reasons.

As I discussed in my last post, the maximum amount of territory the Palestinian side ever demanded for a state encompassed a mere 22 percent of Mandatory Palestine, leaving Israel with the remaining 78 percent. The Clinton Parameters would have tilted the division even further in Israel’s favor. This fact alone should dispel the notion that the Palestinians were the ones who were being unreasonable.

But let’s leave that aside for the moment and consider the foregoing narrative on its own terms—that Israel accepted the Clinton parameters “with reservations” while the Palestinians rejected them. Recently-declassified documents from Israel’s state archives reveal it to be a lie. Both Israel and the Palestinians, it turns out, accepted portions of the parameters and rejected others; there was no meaningful difference in the magnitude of the objections from either side. So this idea that the Palestinian delegation deserves all or even most of the blame for the negotiations’ failure is entirely false.

Not that it is relevant in any case. Israel is free to give the Palestinians a state at any time. It can withdraw its military and illegal settlements from the West Bank. It can grant the West Bank and Gaza unfettered sovereignty over their economic resources and administrative functions along with their land, sea, and air access. There is little to no need for actual negotiations. The problem is that Israel does not want a Palestinian state.

But Why No Ukrainian Hamas?

Another objection I’ve encountered is that the absence in Ukraine of any equivalent to Hamas renders the two cases incomparable. No Ukrainian of any significance has called for the genocide of Russians or the destruction of the Russian state. There is no Ukrainian terrorist organization that targets innocent Russian civilians. The point of those who promote this line of argument is that Ukrainians are somehow more deserving of a state than are Palestinians, and that Israel, unlike Russia, is justified in maintaining its occupation.

It is true that Ukraine does not seek to wipe Russia off the map. It is also true that Hamas has long espoused genocidal aims toward Israelis. Judging by its terrorist attack of October 7th, it still does.

But those who advance such rationalizations imply that the difference is attributable to some sort of character flaw on the Palestinians’ part and which is absent among Ukrainians. This is nonsense. No self-respecting social scientist or historian would accept the notion that variations in political behavior from one society to the next are attributable to differences in fixed cultural traits; this sort of thinking died out in the 1960s. The fact that Palestine has produced a Hamas while Ukraine hasn’t is due not to the respective characters of the two peoples but the different circumstances facing each.

To understand why, imagine if Russia won its war against Ukraine and permanently occupied it. Imagine further that it deported a huge segment of Ukraine’s population and kept the remainder under a repressive, violent, and generally humiliating occupation—as state media and top Kremlin officials have openly pledged to do. Then imagine that this situation persisted for decades thereafter.

Is it conceivable that there might arise under these conditions a Ukrainian terrorist organization with a genocidal ideology targeting Russians? Is it possible that this organization would carry out deadly attacks against innocent Russian civilians? And that Russia would treat said organization as a serious security threat and respond by tightening the chains of oppression on Ukraine?

Of course it is.

The Inescapable Logic of Occupation

The fact that there is no Ukrainian Hamas has nothing to do with the superior character of Ukrainians but the different circumstances they face as compared to the Palestinians—namely, a decades-long and highly-institutionalized occupation in the latter case and the absence, as of yet, of decades-long and highly-institutionalized occupation in the former.

This is one of the key differences between Palestine and Ukraine. It both explains the different dynamics of the two conflicts and serves as a warning of what failure in Ukraine would mean. Occupation in Palestine is longstanding and institutionalized. The mass-deportation of the original inhabitants has already occurred and is likely permanent. The mechanisms of control are firmly rooted and routinized. This combination of factors has severely weakened the occupied population’s capacity to resist. As a result, ending the occupation is largely up to the occupier’s own discretion and, in particular, the costs it is willing to bear in order to maintain it.

But in Ukraine, the occupation is not old. Nor is it institutionalized. It is new and tenuous. Permanent occupation is a long way off, if it is possible at all. Consequently, Russia, unlike Israel, has not had a chance to lay down stable structures of domination in the parts of Ukraine it controls. Doing so would at a minimum require the sort of large-scale population-displacements Israel was able to engineer decades ago. But Russia will remain incapable of pulling that off absent a decisive military victory or, at the very least, a stable stalemate.

Ukraine, for its part, can avert such a scenario so long as it retains an actual state with a capable military, something Palestine lacks. As long as this situation persists, moreover, there will be no need on the Ukrainian side for a non-state or quasi-state actor like Hamas which engages in asymmetrical warfare.

Differences in the length and institutionalization of the two occupations also helps explain another oft-noted distinction between Ukraine and Palestine: Namely, that Israeli forces, unlike Russia’s, do not engage in mass-executions, sexual violence, or ethnic cleansing against the occupied population.

But again, to the extent that this is true, it is not attributable to some immutable cultural difference between Israelis and Russians. Israel certainly used to rely on such brutal tactics before it had consolidated its control over the Palestinian territories; this, after all, is what the logic of imposing occupation typically demands, at least in the eyes of the occupying power.

During the years immediately preceding and following Israel’s founding, its forces carried out deliberate mass-killings of Palestinians on a regular basis. Examples include the attacks on al-Khisas (1947), Balad al-Shaykh (1947), Abu Shusha (1948), Deir Yassin (1948), Lydda (1948), Ein al Zeitun (1948), al-Dawayima (1948), Qibya (1953), Khan Yunis (1956), Kafr Qasim (1956), and Rafah (1956).1 In several of those cases, including Abu Shusha, Deir Yassin, Lydda, and al-Dawayima, Israeli forces faced credible allegations of rape and other forms of sexual violence.

Ethnic-cleansing, too, was a notorious feature of Israeli occupation during this period. Around 700,000 of the approximately 1.2 million Palestinian residents of Mandatory Palestine were displaced from their homes in 1948. There is some debate regarding how many were directly expelled by Israeli forces versus the number which left because of other factors, such as the anticipation of Jewish violence or the example of Arab elites who had already sought refuge abroad.

Historians also disagree over whether the flight of the refugees was part of some master plan or instead resulted from the independent initiative of certain Israeli units. Scholars like Ilan Pappé see evidence of a top-down policy of ethnic cleansing. Others like Benny Morris argue the expulsions were an improvised, ad-hoc response to evolving conditions on the ground—namely the invasion of the Arab coalition.

But even Morris acknowledges that a large number of Palestinians, if not a majority, fled in response to deliberate actions by Jewish forces, whether through direct orders to leave or from fears prompted by the 20-odd massacres Jewish organizations perpetrated against Palestinian civilians in 1947-48.

Most scholars also agree that the flight of the Palestinians was both desired by Zionist leaders in the years leading up to the event and rendered permanent afterwards, when the newly-established state used violence and intimidation to prevent their return.

Less well known but no less important than the expulsions of 1948 were the ones that followed the 1967 war. During and after that pivotal summer, Israeli forces expelled hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from East Jerusalem, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and the Golan Heights. Included among the victims were many refugees who had already suffered deportation in 1948.

What renders such brutality a common feature of early-stage occupation is the enduring institutional strength of the enemy population. This induces a sense of vulnerability and fear on the part of the occupier, which in turn makes unrestrained violence appear both necessary and permissible. After all, as frequent as the aforementioned massacres by Israel were, they were seen in large part as retaliation for similar atrocities by Arab organizations, which at the time were still strong enough to carry them out on a regular basis. Once the occupation had been firmly established, however, the imperative for such barbaric acts became weaker, allowing for more “civilized” forms of repression.

Unfortunately, the terrorist attacks of October 7th pierced this longstanding perception of security. For the first time in many years, Israelis cannot go about their daily lives while remaining happily oblivious to the millions of occupied Palestinians in their midst.

This fact goes a long way toward explaining the eliminationist rhetoric from top Israeli leaders as well as the dramatic increase in the indiscriminate character of the IDF’s aerial bombings. With the return of a sense of existential dread has come a resurgence of the genocidal impulse. As a result, the danger that Israeli forces will resort to mass-killings and large-scale ethnic cleansing is greater than at any point since the 1960s.

Toward Moral Clarity

Sorry, but it is not logically possible to hold “Russian occupation bad” and “Israeli occupation okay” in your head simultaneously. The reverse proposition—that Israeli occupation is bad but Russian occupation acceptable—is just as untenable.

The reason is simple: Occupation can almost never be imposed or maintained without inflicting systematic human rights abuses on the occupied population. Its basic logic inherently requires, or is seen as requiring, acts of unspeakable evil. This is true regardless of how virtuous you think the occupier happens to be.

Palestine is not Nazi Germany and Ukraine is not imperial Japan. Neither one has both the intention and ability to brutally subjugate others and must itself be occupied to avert such a scenario. Unless and until there arises some regional power somewhere in the world which actually meets those criteria, basic morality demands that we oppose occupation—wherever and whenever it occurs.

For more on these and other cases, see Benny Morris, Israel’s Border Wars, 1949-1956 (Oxford: Oxford, 1997). Note: The al-Khisas and Balad al-Shaykh massacres of 1947 were carried out not by the State of Israel, which did not yet exist, but rather by the Haganah, the main Jewish paramilitary organization.

Really good. Check mine out: https://josephgrosso.substack.com/publish/posts

Banana