Propaganda and Collusion in the Trump-Russia Affair, Part 4

No, THIS is what collusion looks like

Photo: Oleg Deripaska at the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, June 16th, 2016. Image used under license from Shutterstock.

“This is what collusion looks like.”

—Democratic Senators Heinrich, Feinstein, Wyden, Harris, and Bennet on the finding that Trump campaign chair Paul Manafort shared internal polling data with reputed Russian spy Konstantin Kilimnik. Quotation appears in an addendum to Vol. 5 of the Senate Intelligence Committee’s report on Russian interference in the 2016 election.

The last two entries in our Russiagate series dealt with the explosive revelation that Paul Manafort, Trump’s campaign manager in 2016, communicated regularly with an alleged Russian spy, Konstantin Kilimnik. The allegation appeared in the fifth and final volume of the Senate Intelligence Committee’s report on Russian interference in the 2016 election. Released in August 2020, the same report disclosed that Manafort passed Kilimnik sensitive internal polling data which might have aided Russia’s interference efforts.

The Senate findings, along with the Treasury Department’s subsequent decision to sanction Kilimnik, prompted longtime collusion-deniers Matt Taibbi and Aaron Maté to reach out to the alleged spy. The resulting interviews, we saw in Parts 2 and 3, exposed the remarkable—and quite intentional—credulity of these supposed skeptics.

Considering they had already staked their reputations on the claim that Russiagate is a silly conspiracy theory, the choice to undertake this exercise in motivated gullibility was the only move they had left.

There is much about Russiagate that is ultimately unknowable. What was the nature of the polling data Manafort passed to Kilimnik? What did Kilimnik do with that information? How much did Russia’s hack-and-leak operation and social media campaign actually influence the election results? It is unlikely we will ever get answers to such questions.

But certain aspects of Russiagate are knowable. Not only that, they dwarf the other parts in importance. Today, we examine such an issue.

The same Senate report that had pundits obsessing over Manafort’s relationship with Kilimnik contained a much more far-reaching revelation, one which elicited comparatively scant notice: Both Manafort and Kilimnik explicitly acknowledged using Manafort’s position to win the favor of a Russian billionaire named Oleg Deripaska.

But here’s the thing: Deripaska is no ordinary billionaire. He is a billionaire who also happens to be a known-proxy of the Kremlin. So by working on Deripaska’s behalf, Manafort and Kilimnik were effectively working on the Kremlin’s behalf as well—a fact of which they were surely aware.

By the time Trump rode down the escalator in 2015, Manafort and Kilimnik had already had a long and contentious history with Deripaska. In 2004, when Manafort was first getting his feet wet in Russia and Eastern Europe, Deripaska emerged as his most significant patron. He also introduced Manafort to Ukrainian oligarch Rinat Akhmetov, thus marking the beginning of Manafort and Kilimnik’s activities in Ukraine.

Manafort’s work for Deripaska proved quite lucrative. In 2006, an Associated Press investigation found, he inked a $10 million-per-year contract with the Russian billionaire to advance both Deripaska’s interests and those of the Kremlin. (Deripaska sued the AP for that story. He lost.)

Eventually, Manafort and Deripaska had a falling-out. By 2016, however, Manafort faced personal bankruptcy and was desperate to restore the relationship. As the following discussion reveals, he aimed to use his campaign role to do just that.

Did any of Manafort’s interactions with Deripaska during the 2016 campaign constitute a crime? Perhaps so, perhaps not. But from a counterintelligence standpoint, it was a potential disaster. Managing a U.S. presidential campaign lends one extraordinary leverage over the candidate’s policy program. If the candidate wins, it offers the chance to influence staffing and policy in the next administration.

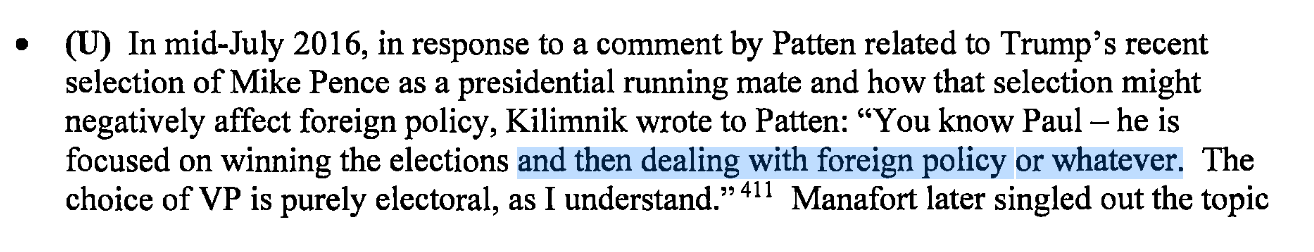

That is exactly what Manafort intended to do. According to Kilimnik, “dealing with foreign policy” was a key priority of Manafort’s in the event Trump prevailed. From the Senate report:

As we will see below, Manafort and Kilimnik did their best to follow through on these ambitions following Trump’s victory. Ultimately, none of their efforts amounted to much. But that’s not the point. The fact is, they could have had Manafort continued on in his position through November.

Fortunately, he did not. In August 2016, he was forced to resign from the campaign. Prompting his ouster, in fact, were his dubious foreign connections—in particular, a scandal involving off-the-books payments he received from Ukraine’s Party of Regions, a Russia-linked looting and pillaging operation masquerading as a political party.

If not for this lucky accident, we could have easily found ourselves on an alternate timeline, one in which Manafort—a man deeply-compromised by his desperation to return to the good graces of a Kremlin billionaire—kept his job and exerted real influence on the Trump administration.

The revelation that Trump’s campaign manager tried to use his position to win over a Kremlin proxy should have attracted far more attention than it did. Compared to this, the whole question of Kilimnik and the polling data is practically irrelevant. But with few exceptions, most media coverage of Volume 5 focused on Manafort and Kilimnik’s relationship with each other while ignoring the links both had with Deripaska.

To be sure, numerous outlets, including TIME, The Atlantic, The Daily Beast, The Washington Post, and The New York Times had already reported on the Deripaska angle as early as 2017. Several other commentators had also covered the story, including Seth Hettena (on Deripaska) and, especially, Marcy Wheeler (on both Deripaska and Kilimnik). So the release of Volume 5 was not the first occasion in which the relevant evidence had been made public. Still, despite the considerable attention the report devoted to both aspects of the affair, its findings on Manafort’s interactions with Kilimnik vastly, and inexplicably, overshadowed those regarding their mutual dealings with Deripaska.

There are two conclusions to draw from all this. First, the idea that Russiagate was a baseless conspiracy theory is bullshit. Second, the finding that Trump’s campaign manager used his position to try and collude with a Kremlin proxy is not mere speculation; it is a fact.

“Our biggest interest”

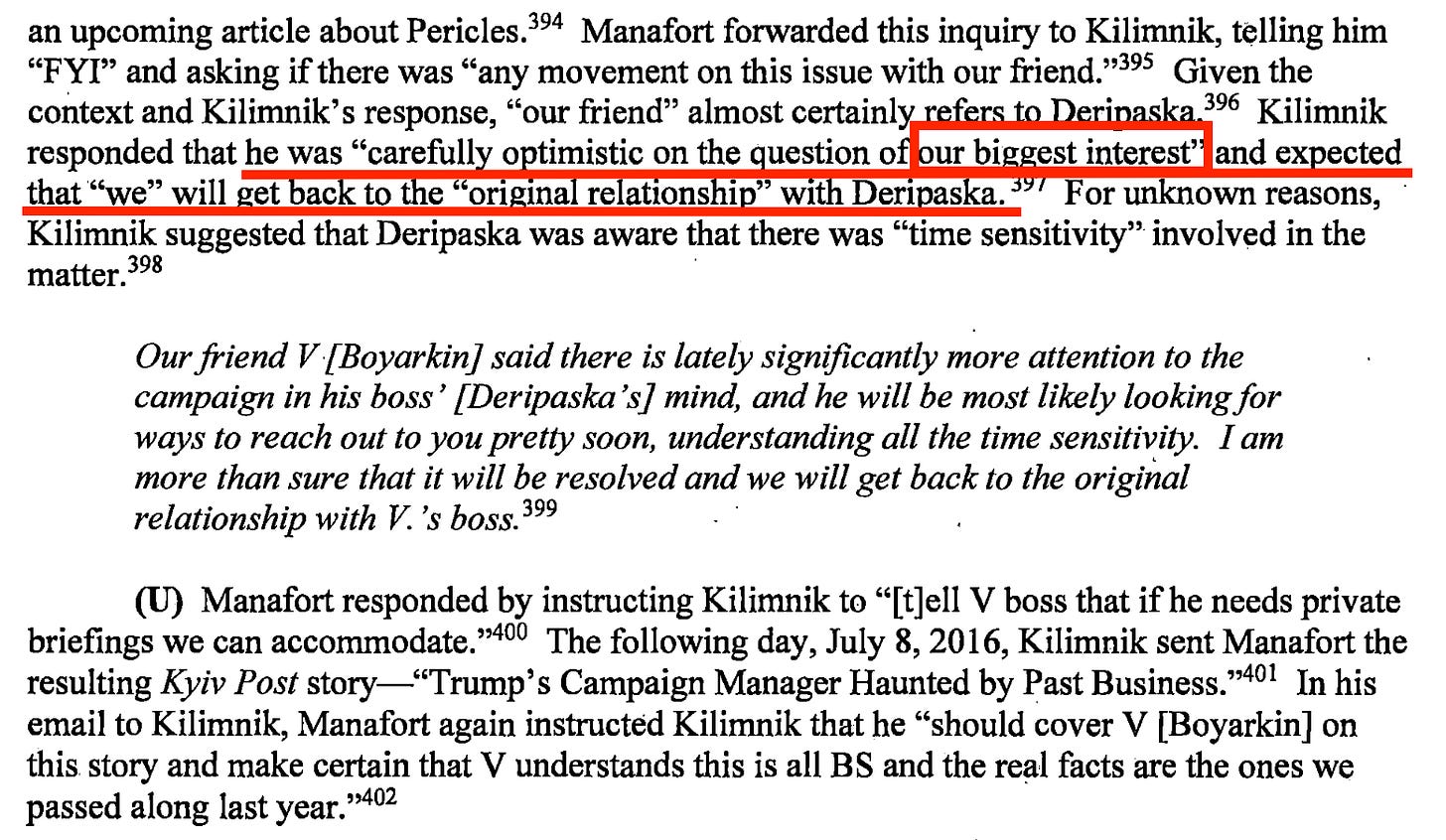

In a July 2016 email to Kilimnik, Manafort brought up the pressing issue of an unpaid debt he owed Deripaska. In truth, it was not so much a debt as it was money that Deripaska believed Manafort had stolen from him. According to the Senate report, Manafort asked Kilimnik

if there was "any movement on this issue with our friend.” Given the context and Kilimnik's response, "our friend" almost certainly refers to Deripaska. Kilimnik responded that he was "carefully optimistic on the question of our biggest interest” and expected that "we" will get back to the "original relationship" with Deripaska.

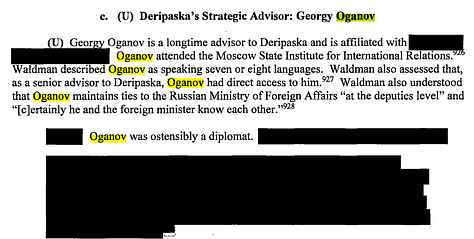

In a later email the same day, Manafort instructed Kilimnik to “[t]ell V boss that if he needs private briefings we can accommodate.” “V” refers to Viktor Boyarkin, an alleged Russian intelligence officer who also serves as a top adviser to Deripaska. Accordingly, “V boss” is a reference to Deripaska himself. Manafort, in other words, is directing Kilimnik to tell Boyarkin that they can offer Deripaska private briefings on the campaign if Deripaska wishes.

The above passage is arguably the most important one in the entirety of the 952-page Senate report. Not only are Manafort and Kilimnik discussing the prospect of mending relations with Deripaska; they acknowledge that the matter constitutes their “biggest interest.”

Yes, you read that correctly: The “biggest interest” of the head of a U.S. presidential campaign was not the campaign itself. Rather, it was to win the favor of a billionaire who acts on the Kremlin’s behalf.

Boyarkin, the Deripaska deputy mentioned above, confirmed as much to a TIME reporter in 2018. The Trump campaign chair “owed us a lot of money,” he said, when asked about his reported communications with Manafort in 2016. “And he was offering ways to pay it back.”

It was this, not his actual job, that served as Manafort’s chief priority while he managed Trump’s presidential bid. It was, quite clearly, the reason he took the job in the first place. For Manafort, the campaign was a sideshow, which is probably why he volunteered to run it for free.

As Manafort and Kilimnik acknowledge, Manafort’s position in the campaign offered him two opportunities he could not afford to pass up: (1) Repaying, in the form of political access, a worrisome debt to Deripaska he was unable to settle in cash, and (2) restoring a lucrative relationship with the Russian businessman at a time when he faced reported bankruptcy.

When Manafort accepted the position, he was in debt to the tune of millions of dollars and had precious little coming in. The flight from Ukraine of his erstwhile sugar daddy, Viktor Yanukovych, during the 2014 Euromaidan protests signaled the end of Manafort’s main source of income. In fact, Manafort would spend the ensuing years trying to recover money owed to him by Yanukovych’s kleptocratic political party, which itself had lost access to the pillaged booty it had once used to compensate him. To make matters worse, a business deal involving Manafort and his conman son-in-law went sour. Last but not least was the debt he owed Deripaska.

So, for Manafort, the Trump job was a godsend; it not only promised to free him from severe financial distress but also held out the prospect of financial security going forward. All he had to do in exchange was deliver the American presidency to Vladimir Putin’s pet-billionaire, Deripaska.

The following passage, also from Volume 5 of the Senate report, contains another set of emails between Manafort and Kilimnik. The exchange demonstrates the importance Manafort placed on exploiting his campaign role to impress his former benefactors in Russia and Ukraine. (Below, “OB” refers to Opposition Bloc, the rebranded Party of Regions in Ukraine previously led by exiled-president Yanukovych. “OVD” stands for Oleg Vladimirovich Deripaska.)

In the exchange, Manafort inquires whether OB’s patrons, namely Ukrainian oligarch Rinat Akhmetov and his partners from Donetsk, have seen the recent press coverage of Manafort. He also wants to know how he might use his campaign position to collect the money OB owes him. “How do we use to get whole?” he asks Kilimnik.

But Manafort also wants Kilimnik to tell him if Deripaska has seen the press coverage. “Has OVD [Deripaska’s] operation seen?” he writes to Kilimnik. In response, Kilimnik confirms he has been "sending everything to [Deripaska deputy] Victor [Boyarkin], who has been forwarding the coverage directly to OVD."

Most revealing, however, is what Kilimnik says next: He has “more hopes for [Deripaska],” he writes, “than for idiotic Ukrainians, who seem to be completely falling apart.”

In other words, Kilimnik is reminding Manafort that their main priority is not OB and its oligarch-backers in Ukraine but rather Deripaska, the Kremlin proxy.

This exchange occurred in April 2016, when Manafort’s campaign responsibilities were limited to marshaling convention delegates for Trump. The previous one I cited took place later, in July. By that point, Kilimnik and Manafort, now chair of the entire campaign, had evidently concluded that Deripaska was, in fact, their “biggest interest.”

This is reflected in the various endeavors they undertook on behalf of Deripaska and the Kremlin both during and after Manafort’s tenure with the campaign. As we saw in Part 3, one of these initiatives involved a Kremlin-backed “peace plan” for eastern Ukraine. According to the Senate report, Manafort and Kilimnik coordinated with Deripaska’s associates on the project, a key goal of which was to secure support from a future Trump administration.

Further underscoring Deripaska’s importance to Manafort and Kilimnik is the value they placed on repairing relations with the Russian billionaire in the wake of Trump’s victory.

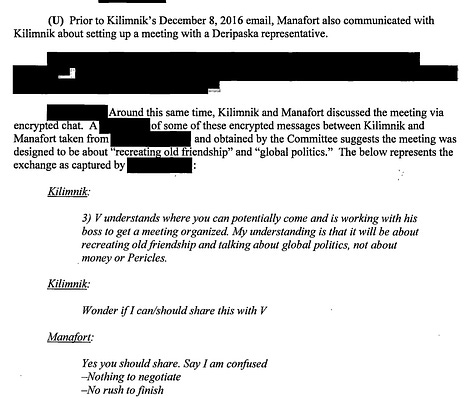

In January 2017, before Trump was sworn-in, Manafort traveled to Madrid to meet Georgy Oganov, one of Deripaska’s top advisers. The idea, in Kilimnik’s words, was “recreating [the] old friendship” with the Russian billionaire. Chief among their objectives was to settle Manafort’s outstanding debt to Deripaska (referred to below as “the Pericles matter”). Oganov informed Manafort that resolving this issue would require a sit-down with Deripaska himself. (Manafort—quite wisely—told Oganov he would not travel to Ukraine or Russia for such a meeting.)

Kilimnik and Manafort also tried to shape the policies and personnel of the incoming Trump administration. The Ukraine “peace-plan” constituted one such line of effort, with Kilimnik angling after the election to get Manafort appointed as Trump’s “special representative” to see the plan through.

Kilimnik also sought to use Manafort to sway Trump’s policy toward Iraq:

Kilimnik additionally tried to secure an administration post for his associate, Sam Patten.

Again, because Manafort had exited the campaign months before, he was effectively out of the loop during the transition period, when many of the key decisions about the incoming administration were being made. By that point, he had been replaced by others who were in a much better position to influence these developments. Still, had he managed to hold onto his post through the election, there is little doubt that he would have been one of the people steering the ship.

So what does it all mean?

It is worth reviewing the main takeaways from this discussion:

When Paul Manafort agreed to serve on Trump’s campaign, he was heavily-indebted and had few, if any, financial prospects.

Among his biggest creditors was Oleg Deripaska, a billionaire Kremlin-proxy.

Manafort, along with his business partner, Konstantin Kilimnik, acknowledged in private communications that restoring their relationship with Deripaska was their “biggest interest.”

During and after Manafort’s time with the campaign, he and Kilimnik provided regular updates to Deripaska’s team. They also worked with the group to advance Deripaska’s agenda along with that of the Kremlin.

During the campaign, Manafort, according to Kilimnik, made clear his intention to influence the foreign policy of a future Trump administration.

Given how vulnerable he was to Deripaska’s leverage and, by extension, that of the Kremlin, it is reasonable to believe that Manafort aimed to direct Trump administration policy and staffing to their advantage, specifically.

Manafort might well have succeeded in all of this had circumstances not forced him to resign months before the election, thus averting a potential counterintelligence catastrophe.

To summarize: Trump’s campaign manager was deeply-compromised by his ties to a Kremlin proxy. He sought to influence the Trump presidency in a way that benefited both the proxy and the Kremlin itself. And he was thwarted from doing so only because of his early-exit from the campaign.

This should have been a much bigger story than it was—far bigger, in my humble opinion, than whatever polling data Manafort gave Kilimnik or what, if anything, the Kremlin ultimately did with it. Not only are these latter questions unanswerable; their importance arguably pales in comparison to the possibility that a bankrupt reprobate in the pocket of a Kremlin stooge might have decisively shaped an American presidency.

This is not a non-story. Nor is it the product of some paranoid liberal fantasy. It involved real people with real influence and dangerous aims who very nearly realized those aims, an eventuality that posed grave consequences for American democracy and national security.

It kind of merits concern, don’t you think?

Next time, we will look beyond Manafort’s attempted collusion with Deripaska to examine what exactly made the Russian billionaire such a threat in the first place. Doing so requires a look into his alleged ties to Russia’s criminal underworld along with his unique relationship with the Kremlin.

Other entries in this series:

Propaganda and Collusion in the Trump-Russia Affair, Part 1

Propaganda and Collusion in the Trump-Russia Affair, Part 2

Propaganda and Collusion in the Trump-Russia Affair, Part 3

Propaganda and Collusion in the Trump-Russia Affair, Part 5

Propaganda and Collusion in the Trump-Russia Affair, Part 6

"There is much about Russiagate that is ultimately unknowable. What was the nature of the polling data Manafort passed to Kilimnik?"

Rick Gates has testified under oath that this was topline polling data showing Trump's performance in surveys, provided in order to maintain his business in the region. It was him showing off about how he'd helped Trump reduce Hillary Clinton's polling lead. Do keep up.

"How much did Russia’s hack-and-leak operation and social media campaign actually influence the election results? It is unlikely we will ever get answers to such questions."

You mean the "Russian hack-and-leak" operation for which there is "no concrete evidence" in the words of Shawn Henry, CEO of Crowdstrike, the only entity to actually look at the DNC servers? On results - https://theintercept.com/2023/01/10/russia-twitter-bots-trump-election/. Do keep up.